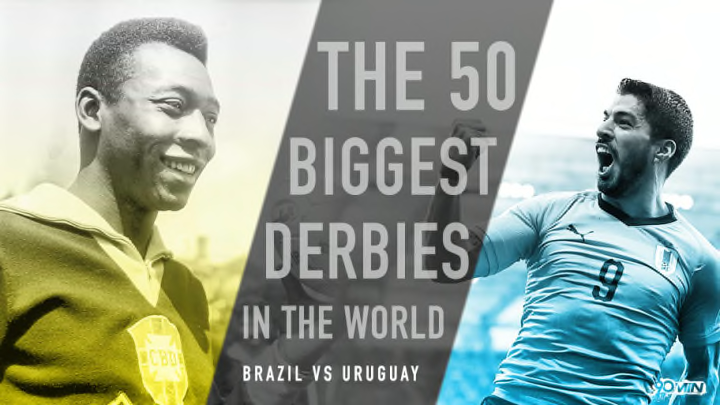

Brazil vs Uruguay: South America's Other Huge International Rivalry

There are more globally talked about rivalries in South American football than this one.

Brazil-Argentina is the obvious example that springs to mind, once described as the ‘essence of football rivalry’ by FIFA. It has been fuelled by the success of both nations at continental and global level, as well as the decades long ‘greatest of all time’ debate surrounding Pele and Diego Maradona.

Argentina-Uruguay is another. The neighbouring countries separated by the mouth of the Rio de la Plata contested the first ever World Cup final in 1930, as well as eight of the first 13 Copa America finals between 1916 and 1935, or the South American Championship as it was then known.

Yet Brazil-Uruguay as a ‘derby’ ranks incredibly highly in terms of significance to the footballing history of both countries. The great Pele described Uruguay as being Brazil’s ‘arch rivals’ alongside Argentina in his 2006 autobiography. That was particularly cemented in 1950.

Brazil and Uruguay is a geographic and population mismatch. The latter is the second smallest country in South America, while the former is the fifth largest in the whole world.

Uruguay is sandwiched between Brazil and Argentina on South America’s Atlantic coast and was even under the rule of the relatively short-lived Empire of Brazil in the 19th century. Even today, its estimated population totals around 3.5m people, compared to 210m in Brazil.

Despite their vast differences, football has been a great leveller.

The rivalry dates back more than 100 years, with the first official game between Brazil and Uruguay taking place in the inaugural South American Championship in 1916. La Celeste beat the Seleção 2-1 in the four-team tournament in Argentina en-route to the title. It marked the start of Uruguay’s early dominance of both continental and global international football.

A year later, Uruguay hammered Brazil 4-0 in the 1917 edition on home soil as they won the trophy again. Brazil gained the upper hand in 1919 when they hosted the Championship for the first time, winning 1-0 in a playoff match to claim the title after the pair had finished level on points in the initial round robin competition – they had drawn 2-2 in the first meeting.

That playoff actually lasted an astonishing 150 minutes as it needed two periods of extra-time to separate the teams, with no replay and long before the introduction of penalty shootouts.

In 1920, Uruguay inflicted a defeat on Brazil that would be the country’s record loss for 94 years until the harrowing 7-1 humiliation at the hands of Germany on home soil in the 2014 World Cup semi-final. That 6-0 win for Uruguay, despite Brazil’s triumph a year earlier, underlined their strength, power, prowess and dominance in the early years of international football.

Uruguay team that beat Brazil 6-0 in a match of the 1920 Campeonato Sudamericano. Their greatest defeat for 94 years pic.twitter.com/ZIfNC1pmWx

— The Antique Football (@AntiqueFootball) July 12, 2014

At that time, Brazil were playing catchup. Uruguay went on to win consecutive gold medals at the 1924 and 1928 Olympics, before then hosting and winning the inaugural FIFA World Cup in 1930. In that tournament, Brazil were denied even a knockout place by Yugoslavia.

Brazil were knocked out of the 1934 World Cup in Italy in round one. But after a much improved display at a global level in 1938, largely thanks to generational superstar Leonidas, Brazil expected to be crowned world champions when they hosted the tournament for the first time in 1950.

Everything was going to plan, until Uruguay intervened and sent a nation into mourning.

Although the meeting between Brazil and Uruguay at the newly constructed Maracanã in Rio de Janeiro has become known as the 1950 World Cup, it wasn’t. The tournament didn’t follow a typical knockout format and was more akin to the early South American Championship round robins.

What it was, was the final game in the second round group stage that coincidentally would decide the winner as they were the two best sides. Spain and Sweden played simultaneously in Sao Paulo and Brazil vs Uruguay might have been irrelevant had things panned out differently earlier on.

Brazil were comfortable in the first round group, but stepped things up to a new level for the next stage. Sweden were thrashed 7-1 in the opening game of the second round, with star man Ademir scoring four – he went to top score at the tournament with eight in total. Then the Seleção ripped apart Spain in a 6-1 demolition in front of an estimated 150,000 people at the Maracanã.

Uruguay had only needed one game to reach the second round due to France’s withdrawal from the first group, and had thrashed Bolivia 8-0. But their second round results were less convincing – a 2-2 draw with Spain and a narrow 3-2 win over Sweden – making Brazil firm favourites.

The hosts only needed a draw against Uruguay in the final game to win a first ever World Cup trophy and satisfy a growing hunger in a football mad nation. But what followed soon became known as Maracanazo, loosely translated to ‘The Agony of Maracanã’.

Things were going to plan for Brazil when Friaca scored early in the second half, only for the tide to change. Uruguay number ten Juan Alberto Schiaffino, who later also played international football for Italy after joining AC Milan in 1954, equalised and silenced a crowd just shy of 200,000.

At that moment, Brazil would still have lifted the trophy, but Alcides Ghiggia wrote his name in sporting history with a little over ten minutes to go, crushing the hopes of a nation. The diminutive winger’s shot squeezed into the net at the near post under goalkeeper Moacir Barbosa.

Alcides Edgardo Ghiggia of Uruguay. Ghiggia scored the goal against Brazil that won Uruguay the 1950 FIFA World Cup. pic.twitter.com/p8gSxkAsA1

— The Antique Football (@AntiqueFootball) June 6, 2014

Barbosa was blamed for the defeat and was scarred by it for the rest of his life. In 2000, shortly before his death, the goalkeeper famously lamented how the maximum jail sentence in Brazil was 30 years, yet he had been ‘imprisoned’ and suffering for half a century.

The emotional scale of the defeat as it was felt in Brazil was truly enormous, almost inconceivably so, and the devastation was even likened by playwright and national treasure Nelson Rodrigues to the atomic bomb dropped that had been dropped on Hiroshima in Japan in 1945.

“Everywhere has its irremediable national catastrophe, something like a Hiroshima. Our catastrophe, our Hiroshima, was the defeat by Uruguay in 1950,” Rodrigues said in 1966.

Recalling his own memories from that day and seeing his father and friends stunned into a zombie-like state, Pele noted in his 2006 autobiography: “The noise of cheers, firecrackers and radios turned up to full volume had disappeared into a void of silence.”

Ghiggia, who died in 2015 aged 88, remarked many years later: “Only three people, with just one motion, silenced the Maracanã, Frank Sinatra, Pope John Paul II and me.”

The lasting impact on Brazil was stark. The decision was made to do away with the white shirts they had always typically worn. A search was launched for a new kit design that was suitably patriotic and utilised all four colours of the national flag, with a competition run by a newspaper seeking entrants from fans. The winning design proposed the yellow shirts with green trim, blue short and white socks we consider iconic today and it was first worn in 1954.

Joining Italy on two triumphs, 1950 remains the last time Uruguay won the World Cup. Their impressive record at continental level continues, however. Their 15 wins in the Copa America, as it became known in the 1970s, is a record – and six more than Brazil’s nine.

But where 1950 ultimately spurred Brazil onto success and three World Cup wins between 1958 and 1970, author Andreas Campomar has argued that it had the opposite effect on Uruguay, suggesting they effectively became ‘lazy’ in victory and moved away from the origins of their success.

In Golazo: A History of South American Football, Campomar writes, “Uruguay’s tragedy was not to be suffocated under the weight of expectation, but by a misplaced faith that they could always rely on a miracle to rescue them – even in the most dire of straits.”

For more from Jamie Spencer, follow him on Twitter and Facebook!